ハイデガー著作リスト、年代順

ハイデガーの思想の流れを追うには、年代順に著作たけでなく、講義録も読む必要があります。バラバラだとわかりにくいので、ひとまず年代順に、これを読めばよいというリストを作成しました。

○1910年から

■全集第1巻『初期論文集』岡村信孝+丸山徳次+ハルトムートブフナー+エヴェリンラフナー訳

○1919年

■第56/57巻『哲学の使命について』北川東子+エルマーヴァインマイアー訳

■第58巻『現象学の根本問題』虫明茂, 池田喬, ゲオルグ・シュテンガー訳

○1920年

■第60巻『宗教的生の現象学』(Phanomenologie des religiosen Lebens)

■第61巻『アリストテレスの現象学的解釈/現象学的研究入門』門脇俊介, コンラート・バルドゥリアン訳

○1922年

■第62巻『アリストテレスのいくつかの論文の現象学的な解釈--存在論と論理学のために』(Phanomenologische Interpretationen ausgewahlter Abhandlungen des Aristoteles zur Ontologie und Logik)

○1923年

■第63巻『オントロギー(事実性の解釈学)』篠憲ニ+エルマーヴァインマイアー+エベリンラフナー訳

■第17巻『現象学的研究への入門』加藤精司・ハルダー訳、創文社

○1924年

■第64巻『時間の概念』(Der Begriff der Zeit)

■第18巻『アリストテレス哲学の根本概念』(Grundbegriffe der aristotelischen Philosophie)

■第19巻『プラトンの「ソフィスト」』(Platon: Sophistes)

○1925年

■第20巻『時間概念の歴史への序説』常俊宗三郎ほか訳

■第21巻『論理学―真性への問い』佐々木亮+伊藤聡+セヴェリンミュラー訳

○1926年

■第22巻『古代哲学の根本諸概念』左近司祥子+ヴィルクルンカー訳

○1927年

■第23巻『トマス・アクィマスからカントまでの哲学の歴史』(Geschichte der Philosophie von Thomas v. Aquin bis Kant)

■第2巻『有と時』辻村公一+ハルトムートブフナー訳

■第24巻『現象学の根本諸問題』溝口兢一ほか訳

■第25巻『カントの純粋理性批判の現象学的解釈』石井誠士+仲原孝+セヴェリンミュラー訳

○1928年

■第26巻『論理学の形而上学的な始元諸根拠』酒井潔, ヴィル・クルンカー訳

■第27巻『哲学入門』(Einleitung in die Philosophie)

○1929年

■第3巻『カントと形而上学の問題』 門脇卓爾, ハルトムート・ブフナー訳

■第28巻『ドイツ観念論と現代の哲学的問題状況』

■第29/30巻『形而上学の根本諸概念:世界‐有限性‐孤独』原栄峰+セヴェリンミュラー訳

○1930年

■第31巻『人間的自由の本質について』齋藤義一+ヴォルフガンクシュラーダー訳

■第32巻『ヘーゲル『精神現象学』』藤田正勝+アルフレドグッツオーニ訳

○1931年

■第33巻『アリストテレス、『形而上学』第9巻1-3――力の本質と現実性について』岩田靖夫+天野正幸+篠沢和久+コンラートバルドリアン訳

■第34巻『真理の本質について――プラトンの洞窟の比喩と『テアイテトス』』(細川亮一+イーリスブフハイム訳

○1932年

■第35巻『西洋哲学の元初』(Der Anfang der abendlandischen Philosophie (Anaximander und Parmenides))

○1933年

■第36/37巻『有と真理』(Sein und Wahrheit)

○1934年

■第38巻『言葉への問いとしての論理学について』

■第39巻『ヘルダーリンの讃歌「ゲルマーニエン」と「ライン」』木下康光+ハインリヒトレチアック訳

○1935年

■第40巻『形而上学入門』岩田靖夫+ハルトムートブフナー訳

■第41巻『物への問い――カントの超越論的原則論に向けて』高山守+クラウスオピリーク訳

○1936年

■『シェリング「人間的自由の本質について」』

■第43巻『ニーチェ、芸術としての力への意志』薗田宗人+セバスティアンウンジン訳

○1936-1938

■第65巻『哲学への寄与――性起について』大橋良介, 秋富克哉, ハルトムート・ブフナー訳

○1937年

■第44巻『西洋的思惟におけるニーチェの形而上学の根本的立場同一なるものの永劫回帰についての教説』

■第45巻『哲学の根本的問い――「論理学」精選「諸問題」』山本幾生ほか訳

○1938年

■第46巻『ニーチェ反時代的考察』

○1939年

■第47巻『「認識としての権力への意志」についてのニーチェの教説』

○1940年

■第48巻『ニーチェ、ヨーロッパのニヒリズム』(薗田宗人+ハンスブロッカルト訳

○1941年

■第49巻『ドイツ観念論の形而上学』菅原潤, ゲオルク・シュテンガー訳

■第50巻『ニーチェの形而上学/哲学入門――思索と詩作』(秋富克哉+神尾和寿+ハンス=ミヒャエルシュパイアー訳、2000/06)

■第51巻『根本諸概念』(角忍+エルマーヴァインマイアー訳、1987/05)

■第52巻『ヘルダーリンの讃歌『回想』』(三木正之+ハインリッヒトレチアック訳、1989/07)

○1942年

■第53巻『ヘルダーリンの讃歌「イスター」』三木正之+エルマーヴァインマイアー訳

■第54巻『パルメニデス』(北嶋美雪+湯本和男+アルフレドグッツオーニ訳、1999/12)

○1943年

■第55巻『ヘラクレイトス』(辻村誠三+岡田道程+アルフレドグッツォーニ訳、1990/12)

○1951年

■第8巻『思惟とは何の謂いか』

○1955年

■第10巻『根拠律』

○1955-1957

■第11巻『同一性と差異』

以下は複数年にわたる論集

○1936-1968

■第4巻『ヘルダーリンの詩作の解明』(濱田恂子+ブッハイム訳)(1936-1968)

○1935-46

■第5巻『杣径』茅野良男+ブロッカルト訳

「芸術作品の起源」「世界像の時代」「ヘーゲルの経験概念」「ニーチェの言葉「神は死せり」「詩人たちは何のために」「アナクシマンドロスの箴言」

○1919-1958

■第9巻『道標』辻村公一+ハルトムートブフナー訳

○1950-1959

■第12巻『言葉への途上』亀山健吉+グロース訳

「言葉」(1950)、「詩における言葉」(1952)、「言葉についての対話より」(1953/54)、「言葉の本質」(1957/58)、「語」(1958)、「言葉への道」(1959)

○1910-1986

■第13巻『思惟の経験から』(東専一郎+芝田豊彦+ハルトムートブフナー訳、1994/07)

○1962-1964

■第14巻『思索の事柄へ』

○1951-1973

■第15巻『ゼミナール』

一部が『四つのセミネール』に

○1910-1976

■第16巻『演説、挨拶、追憶、祝辞、呼びかけ』

ハイデガーと弟のフリッツの対話の記録

ハイデガーと弟のフリッツの対話の記録が発表された。これを読むと、ハイデガーが確信的なナチスシンパだったことが明らかになるという。

Heidegger en grand frère nazi

La correspondance entretenue par le philosophe Martin Heidegger avec son frère Fritz, dont des extraits viennent d’être publiés, renforce l’idée qu’il fut un nazi de conviction.

LE MONDE | • Mis à jour le |Par Nicolas Weill

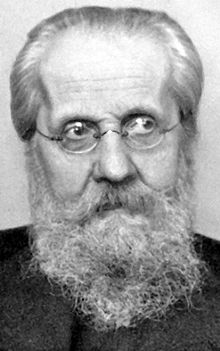

Décidément, le fonds Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), déposé dans les Archives littéraires allemandes (Marbach, Allemagne), n’en finit pas d’alourdir un dossier : celui de l’engagement du philosophe dans le nazisme. En 2013, la publication des Cahiers noirs, ses notes personnelles (encore non traduites en français dans leur intégralité), avait soulevé un coin du voile. Mais la correspondance que l’auteur d’Etre et temps a entretenue avec son jeune frère de cinq ans plus jeune (il meurt en 1980) se révèle plus éclairante encore.

Fritz Heidegger était employé de banque. Il était resté à Meßkirch où leur père avait exercé la profession de sacristain. Une sélection de lettres s’apprête à paraître en allemand aux éditions Herder (Fribourg-en-Brisgau, Bâle, Vienne). Elles sont éditées par Walter Homolka, rabbin réformé, et Arnulff Heidegger, petit-fils de Martin Heidegger, gestionnaire des droits sur l’œuvre de ce dernier, et sont complétées par des contributions de spécialistes, le tout paraissant sous le titreHeidegger und Antisemitismus. Positionen im Widerstreit (« Heidegger et l’antisémitisme. Positions en divergence »). L’hebdomadaire Die Zeit du 13 octobre 2016 consacre deux pages de son « Feuilleton » à des citations et des extraits.

Dans ce qui nous est donné à lire, Heidegger offrira à Fritz, en guise de cadeau de Noël, Mein Kampf. Fritz n’est, en 1931, pas attiré par le nazisme et reste attaché au parti catholique (Zentrum) ainsi qu’au chancelier Heinrich Brünning (1885-1970), lequel a cherché par des moyens autoritaires à sauver la République de Weimar, l’aîné écrit :

« J’aimerais beaucoup que tu te confrontes au livre d’Hitler, aussi faibles soient les chapitres autobiographiques du début. Que cet homme soit doté, et l’ait été si tôt, d’un instinct politiqueinouï et sûr, quand nous étions tous dans le brouillard, personne de sensé ne saurait le contester ».

A propos de la « manœuvre de Papen », la dissolution, à l’instigation de von Papen, du Reichstag, où les nazis viennent d’entrer en force pendant l’été 1932, il écrit :

« Dès le mois d’août [1932] il était clair que tous les Juifs (…) reprenaient la main et se libéraient progressivement de l’état de panique où ils se trouvaient. Que les Juifs aient réussi une manœuvre comme l’épisode Papen montre bien combien il sera en tout cas difficile de s’imposer face à tout ce qui est Grand capital et à tout ce qui est grand… ».

Carte du parti national-socialiste

Après la prise du pouvoir par Hitler, le 30 janvier 1933, l’universitaire se plaint du surcroît de travail qu’entraîne « la disparition de trois Juifs de son département ». Le 4 mai, il annonce fièrement qu’il a pris sa carte du parti national-socialiste (qu’il conservera jusqu’en 1945),

« non seulement en raison d’une conviction intérieure, mais aussi conscient que c’est la seule voie pour rendre possible une purification et un éclaircissement du mouvement [nazi] ».

Il enjoint à son frère de se préparer, au moins « intérieurement », à franchir le pas. Après la défaite de l’Allemagne, le philosophe écarté très temporairement de son université maugrée d’avoir dû loger des anciens détenus des camps (« KZ-Leute ») en juillet 1945. A la même époque, il semble peu craindre la commission d’épuration formée par les troupes d’occupation françaises : les politiciens catholiques (Zentrumspolitikern) seraient à la tête de la « campagne de dénigrement ».

Il trouve que « tout est pénible et pire qu’à l’époque nazie » tandis que ses fils, soldats sur le front de l’Est, sont prisonniers des Russes. En 1946, il estimera que l’expulsion des Allemands des régions de l’Est de l’Europe a atteint un summum en « atrocité criminelle organisée » et « survient indépendamment (…) de ce que nous avons “subi” entre 1933 et 1945 ».

Dans ces extraits, la nostalgie de la bourgade natale et du pays souabe, lieux de l’« enracinement », se donne libre cours en prenant un sens délibérément politique. Ce qui demeure, de ces enthousiasmes nazis, dans la philosophie, reste à déterminer.

リッケルト『認識の対象』を読む(3)

以下では、リッケルトのこの『認識の対象』を原文対照で読んでいくことにしよう。ただし原文は、この書物の第一版であり、邦訳は第二版の訳である。ときおり、第二版の内容を追加しつつ読むことにする。

邦訳で参照したのは次の書物である。

認識の対象 (岩波文庫)

認識の対象 (岩波文庫)

Die Frage jedoch ist nicht eindeutig. Es bedarf sowohl der Begriff des Bewußtseins, als der der Außenwelt, als endlich auch die Art, wie das Verhältnis zwischen beiden gedacht werden soll, einer Erörterung, um genau festzustellen, was eigentlich von der Erkenntnistheorie in Zweifel gezogen wird. Die philosophische Sprache bedient sich nämlich, um den Gegensatz des Bewußtseins zur Außenwelt zu bezeichnen, unter anderem auch der Ausdrücke Subjekt und Objekt, und diese beiden Wörter werden zugleich zur Bezeichnung zweier anderer Verhältnisse gebraucht, deren Verwechslung mit dem hier in Frage kommenden Gegensatz die Hauptquelle der Verwirrung ist, welche bei der Behandlung unseres Problems entstanden sind. Wir werden daher einen dreifachen Gegensatz des Subjekts zum Objekt konstatieren, um den Gegensatz, welcher dem Problem der Transzendenz zu Grunde liegt, genau von den beiden anderen Subjekt-Objekt-Verhältnissen zu trennen.

Das Wort Außenwelt enthält eine räumliche Beziehung. Es kann darunter die Welt im Raume außer mir verstanden werden, und das, wozu dann die Außenwelt in Gegensatz gebracht wir, ist mein Körper nebst meiner "Seele", die in dem Körper tätig gedacht wird; denn nur zu etwas Räumlichem kann die räumliche Außenwelt in Gegensatz stehen. Mein beseelter Körper ist in diesem Falle das Subjekt, die ihn umgebende Welt ist das Objekt. Wir wollen dieses Verhältnis, wenn ein Mißverständnis möglich sein sollte, stets ausdrücklich als das des körperlichen Subjekts zur räumlichen Außenwelt bezeichnen.

In die Außenwelt aber kann ich auch meinen Leib mit hineinrechnen, ich kann alles dazu rechnen, dessen Dasein ich als ein von meinem Bewußtsein Unabhängiges annehme, d. h. sowohl die gesamte physische Welt, als auch alles fremde geistige Leben, gleichviel ob ich dies letztere als irgendwo im Raume seiend, oder als unräumlich betrachten will. Als nicht zur Außenwelt gehörig bleibt dann übrig mein geistiges Ich mit seinen Vorstellungen, Wahrnehmungen, Gefühlen, Willensäußerungen usw. Mein Bewußtsein und sein Inhalt ist also in diesem Falle das Subjekt, und Objekti ist alles, was nicht mein Bewußtseinsinhalt oder mein Bewußtsein selbst ist. Wir werden diesen Gegensatz des Subjekts zum Objekt mit den Ausdrücken der immanenten und der transzendenten Welt bezeichnen, besonders das Objekt in diesem Sinne stets das transzendente Objekt nennen.

さらに身体を考察してみると、精神にとっては身体もまた外界の一部である。自己の意識から独立して存在するものはすべて外界と考えることができる。これには身体も、世界の事物も、他者の精神生活も含まれるのである。内界に含まれるのは、表象、知覚、感情、意思などの自己の精神的な自我だけである。この場合には主観であるのは自己の意識とその内容であり、客観とはこれ以外のすべてのものである。これは「内在的世界と超越的世界の関係」と呼べるだろう。

Zu diesen beiden tritt nun noch ein dritter Gegensatz hinzu. Er liegt nämlich innerhalb des Bewußtseins und entsteht, wenn man das zweite Subjekt noch einmal in Subjekti und Objekt zerlegt. Objekte sind dann meine Vorstellungen, Wahrnehmungen, Gefühle und Willensäußerungen, und ihnen steht gegenüber das, was die Wahrnehmungen wahrnimmt, die Gefühle fühlt und den Willen will. Objekt ist in diesem dritten Falle der Bewußtseinsinhalt, und Subjekti dasjenige, was sich dieses Inhalts bewußt ist. Dieser Gegensatz ist vor Verwechslungen mit den beiden anderen geschützt, wenn er mit den Worten Bewußtsein und Bewußtseinsinhalt oder immanentes Objekt bezeichnet wird.

□まとめ

Wir haben als für das Wort Objekt drei Bedeutungen festgestellt:

- 1) die räumliche Außenwelt außerhalb meines Leibes,

2) die gesamte an sich existierende Welt oder das transzendente Objekt,

3) der Bewußtseinsinhalt, das immanente Objekt. - 三つの対立関係は次のように表現できる。まず客観として、次の三つのものが考えられる。

一)自己の身体以外の空間的な外界

二)全体の自存的世界、すなわち超越的客観

三)意識内容、すなわち内在的な客観

- 1) mein Ich, bestehend aus meinem Körper und der darin tätigen "Seele",

2) mein Bewußtsein mit seinem Inhalt,

3) mein Bewußtsein im Gegensatz zu seinem Inhalt. - 次に主観として、次の三つのものが考えられる。

一)自己の身体と、その内部にある精神

二)全内容を含む自己の意識

三)意識の内容とは区別された自己の意識

第一の立場は、空間を満たすものの他には主観を認めないものであり、唯物論に導かれる。第二の立場は、純粋な内在論であり、これは絶対的な観念論に導かれる。第二の立場にも、この両方の立場に分岐することになる。

Welcher dieser drei Gegensätze liegt nun unserem Problem zu Grunde? Der Dritte des Bewußtseins zum Bewußtseinsinhalt? Ich weiß von einem Sein meiner selbst nur, insofern ich mir einer Vorstellung bewußt bin. Daß mein Bewußtsein einen Inhalt hat, ist also das sicherste Wissen, das ich mir denken kann. Auch ist, wie WUNDT (4) sagt, gewiß jedes Vorstellungsobjekt an und für sich nicht nur Vorstellung, sondern auch Objekt. Aber es ist eben doch nur Vorstellungsobjekt, also Bewußtseinsinhalt. Was Objekt ist, ist darum nicht "objektiv" im Sinne von unabhängig vom Subjekt. Wir unterscheiden zwischen immanenten und transzendenten Objekten, und nur das Sein der immanenten Objekte ist nicht zu bezweifeln. Unsere Frage wird also durch den Hinweis darauf, daß uns Vorstellungsobjekte unmittelbar gegeben siund, gar nicht berührt.

第三の立場は、問題にならない。いかなる認識概念も、この対立なしでは成立しないからである。われわれはある表象を意識したときにだけ、自己の存在を知る。意識が内容をもっているということ、内在的な客観があるということは、最も確実な知識であり、このことに懐疑を適用することはできないである。

Liegt in unserem Problem vielleicht der erste Gegensatz von körperlichem Ich und räumlicher Außenwelt zugrunde? Auch dieser nicht. Denn auch hier gehen wir ja in Wahrheit ebenso wenig wie vorher über Tatsachen des Bewußtseins hinaus. Nur der Unterschied ist vorhanden, daß, während dort die Bewußtseinsinhalte ausdrücklich als solche aufgefaßt wurden, sie hier als selbständige Dinge gedeutet werden und ohne Schaden gedeutet werden können, weil diese Deutung an ihrem Verhältnis zu einander gar nichts ändert. Die räumliche Außenwelt existiert nicht mehr und nicht weniger gewiß, als mein körperliches Ich existiert. Auf welchem Standpunkt man auch stehen mag, niemals wird man beide in Bezug auf die Art ihres Seins in einen Gegensatz zueinander bringen können. Was über ihr Verhältnis zu sagen ist, gehört in die Naturwissenschaften und in die Psychologie.

Die "Außenwelt" also, nach deren Existenz wir fragen, kann weder die räumlich außerhalb meines Körpers gelegene, nocht die als unmittelbar gegebenes Objekt innerhalb meines Bewußtseins liegende Welt sein. Es bleibt nur nich die Welt außerhalb meines Bewußtseins übrig, gegen die sich der Zweifel richten kann. Unsere Frage können wir jetzt auch dahin formulieren, ob das erkennende Bewußtsein es nur mit immanenten oder auch mit transzendenten Objekten zu tun hat.

お勧めのハイデガー入門書

ハイデガーを読み始める人のために入門書を紹介したい。

ハイデガー全般について、この三冊を読もう。

ハイデガー / 木田元著 岩波書店 , 2001.11. - (岩波現代文庫 ; 学術 ; 67)

ハイデガー / 木田元著 岩波書店 , 2001.11. - (岩波現代文庫 ; 学術 ; 67)

目次

序論(『存在と時間』との出会い;ハイデガーの生涯 ほか)

第1章 『存在と時間』について―「世界内存在」の概念を中心に(存在論と現象学;存在論への通路としての人間存在 ほか)

第2章 「時間と存在」の章をめぐって(「時間と存在」の章;『現象学の根本問題』 ほか)

第3章 哲学史への新たな展望(『ニーチェ』講義;「力への意志」の哲学 ほか)

ハイデガー : 存在の歴史 / 高田珠樹 [著]: 講談社 , 2014.10. - (講談社学術文庫 ; [2261])

ハイデガー : 存在の歴史 / 高田珠樹 [著]: 講談社 , 2014.10. - (講談社学術文庫 ; [2261])

内容説明

存在が荒々しく立ち現れると同時に隠蔽され忘却されていった古代ギリシャ以来、存在把握は劇的 に変動し、現在、忘却の彼方に明滅するものとしてのみ存在は現前する―。存在論の歴史を解体・破壊し、根源的な存在経験を取り戻すべく構想された『存在と 時間』の成立過程を追い、「在る」ことを根源的に捉えようとしたハイデガーの思想の精髄にせまる。

目次

序章 ギリシャの旅

第1章 カトリックの庇護の中で

第2章 葛藤と模索

第3章 雌伏の時代

第4章 『存在と時間』

第5章 ナチズムへの加担と後年の思索

ハイデガー : 存在の謎について考える / 北川東子著 日本放送出版協会 , 2002.10.

ハイデガー : 存在の謎について考える / 北川東子著 日本放送出版協会 , 2002.10.

目次

1 存在にどう取り組むか―方法の問題(「存在そのもの」について考える;「意味」の解明を試みる;根本的な問いを考える)

2 「自分が存在している」という事実をどう捉えるか(「自分」というのはなにか;自分は、「世界のうちにいる存在」である;「世界のうちにいる」とはどのようなことか)

3 時間性の問題―「存在の意味」とは「時間性」のことである

次は『存在と時間』の入門書を三冊。

ハイデガー「存在と時間」入門 / 渡邊二郎編: 講談社 , 2011.11. - (講談社学術文庫 ; [2080])

ハイデガー「存在と時間」入門 / 渡邊二郎編: 講談社 , 2011.11. - (講談社学術文庫 ; [2080])

哲学者マルティン・ハイデガーの主著にして、二十世紀の思想界に衝撃と多大な影響を与え、現代 哲学の源流として今なおその輝きを増しつづける現代の古典『存在と時間』。その新しさのゆえに難解とされてきた、ハイデガーが企図した哲学の革新性とはな にか?西洋近現代哲学研究の泰斗と気鋭の後進が精緻かつ平易に解説する、ハイデガー哲学入門。

目次

第1章 『存在と時間』の基本構想(『存在と時間』の主題設定;『存在と時間』の課題と計画;『存在と時間』の方法態度)

第2章 現存在の予備的な基礎的分析(その1)(現存在分析論の端緒;世界の世界性;世人)

第3章 現存在の予備的な基礎的分析(その2)(内存在そのもの;気遣い;存在と真理)

第4章 現存在と時間性(その1)(現存在の全体存在;現存在の本来的な存在;現損存在の本来的な全体存在と時間性)

第5章 現存在と時間性(その2)(本章の課題と構成;時間性と日常性;時間性と歴史性;時間性と通俗的な時間概念)

リッケルト『認識の対象』を読む(2)

リッケルトの『認識の対象』は、ハイデガーがその著作で何度も引用している書物である。リッケルトはハイデガーを指導した教師であり、ハイデガーはリッケルトによって論理学の手ほどきをうけたことを感謝している。ハイデガーを理解するためには、リッケルトの新カント派の認識論を学ぶ必要があるだろう。

以下では、リッケルトのこの『認識の対象』を原文対照で読んでいくことにしよう。ただし原文は、この書物の第一版であり、邦訳は第二版の訳である。ときおり、第二版の内容を追加しつつ読むことにする。

邦訳で参照したのは次の書物である。

認識の対象 (岩波文庫)

認識の対象 (岩波文庫)

第一章 認識論的な懐疑、続き

Dieser Gedanke ist noch heute maßgebend, wenn er auch bei DESCARTES nicht ganz rein auftritt. Die wirkliche Unzufriedenheit mit dem Zustande der Wissenschaften ist nämlich kein sachlich unentbehrlicher Bestandteil, sondern war nur die psychologische Veranlassung, die das Problem zum Bewußtsein brachte. Es muß dies hervorgehoben werden, weil auch heute noch (z. B. VOLKELT) auf die Unsicherheit der Resultate in den Einzelwissenschaften hingewiesen wir, um die Notwendigkeit eines radikalen Zweifels darzutun, und dadurch der Schein entstehen kann, als beabsichtige die Erkenntnistheorie, einen Maßstab an das von den einzelnen Wissenschaften Errungene anzulegen und eventuell die wissenschaftlichen Resultate auf ihren wahren Wert zurückzuführen.

デカルトの懐疑の理由そのものに問題がある。科学的な知識の疑わしさを根拠に、懐疑を始めるべきでないのである。現在でも科学の成果の不確実さを理由に、懐疑の必要性を主張する人がいるが、こうした説は自然科学者が拒否すべきである。

Einen solchen Anspruch würden die Männer der Einzelwissenschaften entschieden und mit Recht zurückweisen. Was die Wissenschaft im Laufe der Jahrhunderte geleistet hat, besitzt seine von jeder erkenntnistheoretischen Untersuchung unabhängige Bedeutung. Nicht das eine oder das andere positive Wissen, sondern die Meinung über das Wesen der Wahrheit selbst, in unserem Falle die Deutung der wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnis als Übereinstimmung unserer Vorstellungen mit einer absoluten Wirklichkeit wird in Frage gestellt.

Es ist nicht abzusehen, wie hierdurch einzelne wissenschaftliche Ansichten, etwa die über die Oberfläche des Mars oder die Funktionen der Großhirnrinde jemals korrigiert oder bestätigt werden könnten, und völlig verkehrt wäre es daher, den Einzelwissenschaften das skeptische Verfahren der Erkenntnistheorie zur Nachahmung zu empfehlen. Die empirischen Wissenschaften müssen "dogmatisch" sein, d. h. eine Anzahl von Voraussetzungen ungeprüft hinnehmen, denn sie würden nicht vorhanden sein, wenn sie es nicht getan hätten.

WUNDT (2) hat Recht, wenn er sagt, daß die ganze Sicherheit des Erfolges, deren sich, bei allen Irrungen im Einzelnen, die Wissenschaften erfreuen, eben darauf beruth, daß sie sich der vollständigen Umkehrung jenes Grundsatzes bedienen, den die "alte" Erkenntnistheorie bei ihren Untersuchungen befolgt hat.

自然科学の成果は、認識論的な研究とはまったく別の意味をもつものである。こうした科学に、認識論の懐疑的な方法を採用せよと主張するのは間違いである。経験科学はつねに独断的であり、いくつかの前提を無批判的に採用するものである。

Trotzdem sagt dies nicht das Mindeste gegen die Berechtigung des skeptischen Verfahren auf erkenntnistheoretischem Gebiet. Nicht nur die "alte", sondern auch die "neue" Erkenntnistheorie kann, wenn sie neben der Psychologie des Erkennens überhaupt noch eine Bedeutung besitzen soll, keine andere Aufgabe haben, als das den übrigen Wissenschaften Selbstverständliche zum Problem zu machen. Deshalb muß auch die Methode ihrer Untersuchung eine eigenartige sein. Wo überhaupt gefragt werden kann, da soll sie fragen. Sie soll, wie man oft schon gesagt hat, im Gegensatz zu den auf ungeprüften Voraussetzungen ruhenden Wissenschaften, voraussetzungslos sein.

しかしこれは認識論における懐疑の重要性を否定するものではない。科学的な研究では前提を無批判的に採用すべきだが、認識論ではそれを問題にしなければならないのである。認識論は無仮定でなければならない。

Allerdings nicht absolut voraussetzungslos, weil ein Denken, das mit nichts beginnen wollte, auch niemals von der Stelle kommen könnte, aber voraussetzungslos in dem Sinne, daß sie ihre Voraussetzungen so weit wie möglich einschränkt. Sie hat, um auf den von Voraussetzungen möglichst freien Standpunkt zu kommen, nur ein Mittel. Sie versucht an allem zu zweifeln. Sie ist dabei nicht geleitet von einer Freude am Verneinen, sondern sie verfolgt nur den Zweck, durch den Zweifel zur höchsten Gewißheit vorzudringen, insofern nämlich, als der nicht ausführbare Versuch zu zweifeln die Voraussetzungen, die allem Wissen zu Grunde liegen, klar stellen muß.

Wie schon DESCARTES einsah, daß die Tatsache des Zweifelns selbst unter allen Umständen unbezweifelbar bleibt, so sucht auch unsere Erkenntnistheorie zu zeigen, welche Voraussetzungen gemacht werden müssen, damit das Zweifeln überhaupt noch einen Sinn hat.

ただし無仮定ということと、絶対に仮定がないということは異なる。認識論は、できるだけ前提を少なくするという意味で無仮定でなければならないのである。無から始めるのでは、永久に思考を実行することはできないだろう。前提を少なくするために、すべてを疑うという懐疑が必要なのである。

Wenn wir den erkenntnistheoretischen Zweifel so verstehen, so kann sein Wert nicht mehr in Frage gestellt werden. Er ist gerechtfertigt als das Mittel, welches zur Entdeckung der unbezweifelbaren Grundlagen unseres Wissens dienen soll. Aber kann auch nur so gerechtfertigt werden. Alle Betrachtungen, welche den Wert erkenntnistheoretischer Untersuchungen durch einen Hinweis auf die Unsicherheit menschlichen Wissens darzutun suchen, sind zum mindesten mißverständlich. Sie entstammen übrigens auch wohl nur selten einem wirklichen Gefühl der Unzufriedenheit, sondern wollen meist nur dem Vorwurf begegnen, daß die Erkenntnistheorie doch eigentlich aus lauter Grübeleien und Spitzfindigkeiten bestehe, die gar keinen rechten Nutzen hätten.

認識論的な懐疑の役割は、知識において疑うことのできない根拠をみいだすために役立つことにある。このように懐疑の範囲を認識論だけに限定し、経験的な科学の成果の確実さに適用しないことによって認識論に固有の範囲を確定することができるようになる。

Es scheint aber, als könne die Erkenntnistheorie gerade diesen Verdacht ruhig auf sich sitzen lassen, und zwar deshalb, weil der Verdacht, jedenfalls in Bezug auf das Transzendenzproblem, sehr begründet ist. Man sollte vielmehr die Zumutung, als müsse durch erkenntnistheoretische Untersuchungen etwas erreicht werden, das eine über ihr eigenes Gebiet hinausgehende Bedeutung hat, entschieden zurückweisen. Es kann ja sein, daß philosophische Untersuchungen im Allgemeinen größere Bedeutung für das gesamte geistige Leben besitzen als manche andere wissenschaftliche Bestrebung. Das wäre ein sehr erfreulicher Nebenerfolg. Verlangen aber darf man einen solchen Nebenerfolg, oder gar irgend einen "Nutzen" auf keinen Fall. Man gebe auch der Erkenntnistheorie das Recht, das jede andere Wissenschaft besitzt, Wahrheit allein um der Wahrheit willen zu suchen.

Gerade dadurch, daß wir den Zweifel auf das erkenntnistheoretische Gebiet einschränken und die Sicherheit der Ergebnisse empirischer Wissenschaften auf ihrem Gebiete unangetastet lassen, gewinnen wir für die Erkenntnistheorie, was man ihr sonst mit Recht bestreiten könnte, ein eigenes Gebiet. Der Zweifel geht weder den naiven Menschen mit seinem Glauben an eine ihn umgebende absolute Wirklichkeit, noch den Mann der Einzelwissenschaften, so lange er nicht zu philosophieren wünscht, irgend etwas an. Er ist lediglich für den Erkenntnistheoretiker ein methodisches Hilfsmittel, das ein rein erkenntnistheoretisches Interesse befriedigen soll. In unserem Fall legt er uns die Frage vor: gibt es eine vom Bewußtsein unabhängige Außenwelt, die Gegenstand der Erkenntnis ist?

懐疑には二つの仕事がある。すなわち誤った認識の概念を破壊することと、正しい認識の概念を建設することである。まず懐疑を一般の仮定に向けて、認識主観の意識から独立した実在、すなわち認識の対象が存在するかどうかを問題にすることにしよう。

土井理代「前期ハイデガーにおける形而上学の遂行」--Webで読むハイデガー論(005)

筆者:土井理代

発表媒体:メタフュシカ

発表年度:2004年12月15日

URL:http://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/11094/9174/1/mp_35_075.pdf

お勧め度: ■■■■

寸評:「存在と時間」刊行後の前期ハイデガーの形而上学の概念を追求し、この時期の思想的な課題をさぐろうとする。

はじめに

ハ イデガーにおける形而上学(Metaphysik)の概念は、 彼の思想全体を通して見れば二義的であるように見える。 確かに彼は西欧的思惟の歴史を形而上学という観点で一括し、 その歴史を存在忘却の極まりゆく一繋がりの展開として批判的に解釈しつつ、それを真に超える「別の思惟」の道を示すことを試みた[1]。

だ が、そのような否定的とも言える形而上学概念が彼の用語法の中で定まってきたのは、彼の思惟の歩み半ば、 1930年代(とりわけニーチェとの対決の途上)以降においてである。 そこで意味される形而上学は、 自然科学の隆盛期であったカントの時代にすでに疑義が表明されていたような伝統的学科としての形而上学とは違い、 われわれの時代にあってもいまだ誰もそこから抜け出せないような包括的な歴史的現象としてのそれであり、 その点で時代批判的、 現代的意義を持つている。

しかし彼が形而上学概念に独自の意味づけを与え直すことを試みたのは、 初めは必ずしもそのような文明批判的な色彩を帯びた否定的な文脈においてのことではなかった。 前期の主著である 『存在と時間』 (前半部)公刊(1927)後、 1920 年代末期のハイデガーにおいて思惟のキーワードとして前面に出された「形而上学」は、やはり伝統的な形而上学概念とは違い、 これから根源的に意味を与えられようとする積極的、 いや少なくとも中立的な概念だった。したがって1930年代以降に歩まれる中期から後期にかけてのハイデガーの思惟から照らせば、この1920年代末期の 形而上学概念は異質なものに見えるのである。

ハイデガーは、 存在忘却という根本経験すら忘却されていく西洋的思惟の支配圏を形而上学と呼び、 そこから外へ出ること (根源へ還ること) を求めた。 しかし一時期彼自身の思惟の表題として形而上学という語が選ばれた。 別の思惟ではなく形而上学という表題が。

以 下の叙述ではこの点に関し、後の形而上学批判はこの1920年代末期の形而上学概念の彫琢を経てこそ理解可能であるこ と、初期から彼の思惟の う ちに強く ある眼前性(Vorhandenheit) の存在論の伝統を解体するという考えが、 基礎的存在論および形而上学の遂行を経て後の形而上学批判へといわば名を変え具体化されていく、 という見通しを持つて、 絡まりの多い前期ハイデガーの思惟の道筋を解きほぐしながら、 そこに内在する問題を指摘することにしたい。

[1 ] 1930年代以降の著作で散見される 「別の思惟 (das andere Denken)」 (WME:381)という言葉は、 内容的には、存在者としての存在者しか表象しない形而上学に対し存在 (原存在Seyn) を問う存在歴史的思惟を指す。

■形而上学の概念の規定

1 現存在と形而上学の分かち難さ

『存 在と時間』(SZ)において人間を現存在(Dasein)と術語化し、 その現存在の分析論としての基礎的存在論を展開 したハイデガーは、 マールブルク大学での講義活動等を通して基礎的存在論を練り直しながら、論文「根拠の本質について」(WG)や著書『カントと形而上学の問題』(KPM) を公表した。 そしてその後再び移ったフライブルク大学での就任講演 「形而上学とは何か」(WM)[2]や講義『形而上学の根本諸概念』(GA29/30)ではいずれも「形而上学」という語がキーワードとして前面に出され ることになった。 この時期がハイデガーの思惟の発展において形而上学期と呼ばれることがあるのもそのためである[3]。 だが、 この時期においてもすでに形而上学概念は、『存在と時間』期における存在論の概念と同様、語としてあるいは形式的概念としては一つであっても、 その意味内実は二義的であった。 すなわち、 伝統的に受け継がれてきた表題としての形而上学と、 これから思惟の遂行によってその内実を与えられようとしている形而上学である。 根こぎにされた形而上学と、 根源へと向かおうとする形而上学。 この二義性とはどのようなものなのか。

1-1 全体への問いとしての形而上学

初期フライブルク時代から哲学の生き生きとし た理念を獲得することを目指してきたハイデガーにとって、 形而上学の概念を蘇らせることは、 単に伝統的な意味での形而上学を復活させることではなかった。彼の求める形而上学は、『存在と時間』で展開された基礎的存在論によって確保された「基礎 (Fundament)」(KPM:225)4に踏み留まりながら、「存在」の理解(投企Entwurf) を本質とする現存在の存在(実存Existenz)だけでなく、その現(世界)において情態的に開示されてくる 「全体において在るもの(das Seiende im Ganzen)」[5]の存在へと問い進めること、そしてその中で同時に自己の存在 (実存) を問い直すことを意味している。 それはすなわち、 この問う者自身と全体において在るものという二つの契機を統一的に保持しつつ、 存在への問いを模索し続けていくことである。

こ のような1929年の形而上学を特徴づける言葉をいくつか引いておこう。 「形而上学とは問うことであり、 その問いにおいてわれわれは全体において在るものの中へ問い入り、 その際問う者であるわれわれ自身も共に問いの中に立てられる」 (GA29/30:13)。 すなわちそれは 「全体へと出て行くと同時に実存を隈なく把捉する、 という二重の意味で全てを含む(inbegriflich)思惟」(GA29/30:13)であり、 「形而上学は現存在における根本生起である」(WM:122;GA29/30:12)。このような 「形而上学は、 人間といったものの事実的実存と共に生起する、 存在者の中への破り入り(Einbruch)における根本生起である」 (KPM:235)。

このように特徴づけられる形而上学とは、 すでに基礎的存在論で明らかにされた現存在の存在体制すなわち世界‐内‐存在(世界への超越)の動性を― それに固有の見えにくさと絶えず闘いながら― 自覚的に (問う態度で) 把捉しつつ、 そこで全体として漠然と経験されることを解明していくことに ほかならない。不安や退屈等の根本気分のうちで、事実として現存在が全体において在るものに (あるいはそのような全体の動性と共におのれを示す無に) 晒される瞬間があるとすれば、 そしてわれわれが個々の存在者に態度をとることができるためにはこのような全体の開示がそのつど共に働いているのだとすれば、 そこからさらに 「現存在はいかにして、 全体において在るものの中へそのように立てられることができるのか。 この 「全体において」 がわれわれを取り囲む時そこでは何が働いているのか」(GA29/30:251)ということ―世界への問い― が形而上学的に問い深められなければならないだろう。

[2] 引用の際は表題を示す略号を用いるが、頁番号はその収録先である『道標』のものである(「根拠の本質について」 も同様)。 なお、 略号WMEはこの講演の20年後に付された序論を示す。

[3 ] 以下ではこの時期を、 上記の著作が出版され、 就任講演が行われた1929年にしばしば代表させる。

[4] 「基礎的存在論(Fundamentalontologie)」は、その遂行性格(形式的暗示という遂行指示性格) から切り離された内実だけが学説として受け取られるべきものではない。ハイデガー自身その点についてさまざまな形で注意しているが、誤解を招きやすいのは 「基礎」および「存在論」という語だろう。学の基礎、あるいは根底[根拠]としての現存在は、『存在と時間』で既に明らかにされているように(根源的な意 味で)有限的、時間的でありそれ自身脱底的である。そのようなものとして自らの実存に耐えつつその現象を隠れから取り出す(むしろ隠れるものとして指し示 す) 歩みは、 たとえ学的体裁をとったとしても (実際とったのであるが) 「体系化」 とは異質である。 それは人間存在を分析しているからといって単に人間学でないことは言うまでもなく、 それ自身一存在論ですらない(cf.WME:380)。 ハイデガーの思惟がやがて単に思惟(Denken)としてしか自己表現しなくなるのは、事柄に即して当然のことと言うべきだろう。

[5] 「全体において在るもの[全体における存在者]」 とは 「ピュシス」概念の再解釈から取り出された意味契機である。 勿論これは諸学の対象領域としての 「歴史」 や 「自然」 のいずれかに該当するものではなく、 むしろ存在者の諸領域成立以前にそのつどわれわれに開示され、そこからそれらが可能となるような全体である。

■伝統的な形而上学概念の批判

1-2 伝統的形而上学への疑義

し かしこの時期のハイデガーは 「形而上学」 という伝統的概念を決して肯定的に評価していたわけではない。 むしろそれが根源語ではないこと、 そして、 アリストテレスにおいてすでに問われるべき事柄として現れていたことへの真の理解のないまま、 文書編纂上の前後関係という外的な事情から生まれた語であること、 「メタ」 の意味が単に 「後で」(post)だけでなく 「超えて」(trans)の意味へ転化した際その「超えて」の意味(どこへ向けて超えるのか、その超えて在るものはどこに、 どのような仕方で在るのか、超えられるものとの関係はどうなっているのか等) が真に統一的に思惟されることのないまま中世のスコラ学において教義的に体系化されてしまったこと、 形而上学を乗り越えたはずの近世以来の認識論 (超越論哲学) もまた、 このような伝統において立ち塞がれ曖昧にされたままの存在理解の上に立つているということ[6 ]等が指摘されつつ、それでも敢えて(もはや「存在論」ではなく)「形而上学」という語が選ばれるに至ったわけだが、 この語の選択およびハイデガーによる新たな意味づけ (1929年段階での) には、彼独特の巧妙さがある。

ちょうど 「現存在(Dasein)」 という伝統的な語に、 存在(Sein) へと開かれている (Da=開示性)、 という独自の意味づけが与えられたように、 「形而上学」 という伝統的な語も、万物(ピュシス)を「超えて」在るという現存在に特有の超越の動性―そのつど世界[7]へ向けて (世界を形成・投企しつつ)、 私自身を、 そして全体において在るものをも共に超え行く在り方― を示すものとして解釈され直している。上にも簡単に見たように、このハイデガーの形而上学概念にとっては、世界‐内‐存在(超越)という存在体制を持つ現 存在の概念がそうであるように、その統一的構造(体系の統一性ではなく実存の統一性)、まさにその全体性が本質的なのである。

[6] 近世的特徴と して、全体― 全体において在るものではなく在るものの総体と して眼前に見出される 「世界」ないし 「自然」― への問いと共に、 問う者自身が問題圏の中心となることが指摘されるが、 その際「自我や意識はまさに最も確実で疑問の余地のない基礎としてこの形而上学の根底に置かれる」 (GA29/30:84)点で、ハイデガーの形而上学とは根本的に区別される。

[7] 現存在の存在体制に属する現象としての世界は、 初期以来ハイデガーにおいて多義的 (多重的) であるが、この時期においては、 それはしばしば現存在自身の目的(Umwillen)の全体性という意味で用いられる。 目的全体性とは現存在の存在可能(その最も極端なものは死ぬという可能性)の全体性のことである。現存在は、現存在として存在する限り、存在へと開かれた その独自の存在様式を引き受けなければならないが、 目的とは、そういう意味で現存在が現存在自身であるために(Umwillenseiner)、ということである(cf.WG:157f.)。

■形而上学の概念の二重性

そ れに対して伝統的な形而上学概念にはそのような統一性が欠けている。 この問題の直接の端緒はアリストテレスにおける第一哲学の二義性のうちに見出される。 アリストテレスは、後に『形而上学』 と題され編纂されることになる論考の中で彼が 「第一哲学」 と呼ぶ探究を性格づけ、それを「存在者としての存在者(オン・ヘー・オン)」への問いと「神的なもの(テイオーン)」 への問いという二重性のうちで示した (第6巻)。 そしてこの二つの契機は、 中世における「一般形而上学」(存在論)と「特殊形而上学」(宇宙論、心理学、神学)[8]の体系化へと発展した。

しかし元々同じ一つの事 柄を特徴づけたものだとしても、 存在者としての存在者―存在者を存在者たらしめるもの (存在者の存在) ― と神的なもの― 全体において在るもの― とは、 ただちに同一視されうるものではない。 確かに両者に共通しているのはそれが存在者を何らかの仕方で「超えて」いるということであり、だからこそ文書編纂時に導入された「メタ」が内容的な意味へ と転化した。だが、個々の存在者を「超えて」いる普遍的規定(或るもの、一性、多性、他者性等の諸範疇) としての存在(本質)は、超感覚的というよりはむしろ非感覚的な方向へ超え出ていると見なされるべきである。

なぜならそれは 「感覚を超えたところに独自の存在者として在るもの」 (GA29/30:68)すなわち中世キリスト教の神のように、 文字通り超感覚的なもの9の方へ「超えて」いるということと同じではないはずだからである。 にもかかわらず、 それらが混同されたまま体系化へ至った形而上学にとっては、 もはやそういった問題が問題として見えない、 とハイデガーは批判する。

で は、 このように問題をはらむ形而上学の二重性はハイデガーにおいてどのように調停されるのだろうか。 ハイデガーはその二重性を、 彼が基礎的存在論において分析した現存在の存在へと重ね合わせる。 すなわち、 存在 (存在者としての存在者) の学という方向と神的なもの (ハイデガーは天空、 包摂するもの、 卓越したもの等と訳す) の学という方向が、 実存と被投性(Geworfenheit)の二重性に対応する問いの方向として解釈される(GA26:13)ことで、 今や形而上学の概念はその統一の基盤を得る。 それによってハイデガーは、 体系の統一性ではない生きられる統一性10を形而上学に確保すると共に、 現存在における根本生起と見なされた形而上学は、全体への問いとして、 その遂行性格を色濃くするのである。

[8 ] 体系の統一性を持たないアリストテレスの『形而上学』が、中世(ハイデガーが重視するのはトマスよりもスアレスである) における体系づけ、 すなわち存在論としての 「一般形而上学」 と、 宇宙 (自然) ・魂 (精神)・神の各領域的存在を扱う 「特殊形而上学」 という区分へともたらされたという歴史的経緯は、 この時期のハイデガーの著作や講義録において頻繁に指摘される(GA24:112;GA26:13,33,223;GA27:245;KPM:2f. 等)。

[9] ハイデガーはここに、形而上学の対象が、位階秩序の差はあれ眼前存在者の一領域(感覚を超えたところに在るもの)として外面化されているのを見る(GA29/30:63f.)。

■存在論的な差異

1-3 差異

こ うして伝統的な形而上学と袂を分かちながら、ハイデガーの形而上学は、 人間という存在者を現存在 (現‐存在) という独自の存在様式を持つ存在者へと変貌させること(Verwandlung) を要求する。人間を現存在へと変貌させる、 とは、後にも見るように、現存在とは本質的に異なった存在様式を持つ存在者から読み取られたと考えられる 「眼前性(Vorhandenheit)」 の概念から自由になること、 われわれ自身をそのような 「存在」概念による平均化から解き放つこと、を意図していると言ってよいだろう。

平 均的な存在理解に基づいて、 人間自身が他の存在者と並んで世界に存在 (眼前存在) する一つの存在者のように見なされる一方でそれが理性や自己意識等の能力を持つているという点で他の存在者から際立たせられても、存在(存在そのもの)に 開かれて在る、 というわれわれ自身に固有の存在様式は捉えられない。 したがってまた、 存在そのものへの問いを遂行するための通路 (現存在) は立ち塞がれたままである。 むしろ、 現存在とはそれ自身世界を開きつつあるもの(世界‐内‐存在) として、そこにおいて存在者の存在があらわになる― 存在者と存在の差異が生起する― 特異な存在者である、 という事実が際立たせられなければならない。

この差異をハイデガーは1927年講義で 「存在論的差異(ontologische Dif erenz)」 と名指し、 その後も再三触れている[11]。 この 『存在と時間』 から形而上学期にかけての現存在を起点とする思惟の遂行の中で、 現存在の存在に関わる根源的現象としていくつかの問題が集中的に取り扱われているが、 それは例えば次のようなキーワードで彩られた問題圏である。 すなわち超越、世界‐内‐存在、存在論的差異、無、自由、有限性、時間性、根本気分、投企等。

ハイデガーにとってそれらはすべて同じ一つの (唯一の) 事柄をめぐっていわばさまざまな角度から照らし出され解釈し出された問題であると言えるが、 なかでも存在論的差異、 すなわち、 存在者と存在との差異― 存在者「として」の存在者へと態度をとることを可能にしているもの― は、存在への問いを模索的に遂行するハイデガーにとって中心的な概念であり続ける。 だが、 例えば1929/30年講義において、すでに「存在論的」という形容詞(「存在論」という概念)の使用自体が躊躇われていることからも窺えるように (GA29/30:521f.)、 われわれが1-2で見たような伝統的存在論においてはこの差異が見て取られることはなかった、 とハイデガーは一貫して主張する。 ここには形而上学というものは存在そのもの (存在者と存在のこの原初的な差異) を思惟したことがないとする後の形而上学批判に通じる見方がある。

[10] 「現存在の形而上学的解釈にとっては現存在の体系など存在しない」(GA29/30:432)。むしろその概念的連関は現存在自身の連関、その歴史の連関である点をハイデガーは強調する。

[11 ] この時期における萌芽的な言及としては例えばGA24:22,109,454;GA26:200;GA27:210,223等を参照。

辻村 公一『ハイデッガーの思索』--ハイデガー論紹介(001)

ハイデッガーの思索

辻村 公一【著】創文社(千代田区)(1991/09発売)

ハイデガーに学んだことのある辻村のハイデガー論。これは「前著『ハイデッガー論攷』以後に種々の機会に、多くは求めに応じて、書かれた論文の集成」(iv)とされている。

第1部 理解と解釈

「思ひ」はハイデガーがルネ・シャールとの友情を記念して送った「思ひ」という文章について、その中で書かれた詩についての詳しい考察を展開したもの。これはハイデガーの「遺言」(215)だという。

「『思索の経験より』についての所見」は、この短い文章の「道」としての思索の体験について、紹介したもの。

「告別」は、逝去したハイデガーが書き残していたヘルダーリンの五つの詩を「ハイデッガーの告別の言葉として解する」(136)文章。これらの詩の考察が中心となる。

「最後の神」は、雑誌『シュピーゲル』に掲載された有名なインタビューで語られた「かろうじて神なるものだけがわれわれを救うことができる」という言葉について、「最後の神」という言葉を手掛かりに、ハイデガーの思考の軌跡を簡単にたどる。

第2部 解釈と批判

「真性と非真性」は、ハイデガーの真理概念を『存在と時間』や中期と後期の作品の中から跡付ける。周知のように、ハイデガーにおいては真理は非真理とつねにともに考察されているが、ここでは著者特有の文体でハイデガーに特有真理概念が考察される。

「静けさの響」は、ハイデガーの言語の理論を、「静寂のうちの響き」という逆説的な表現から探ろうとするもの。

「ハイデッガーと技術の問題―或る一つの批判的所見」 は、ハイデガーの技術論を「ゲシュテレ」の概念を軸として考察する。結論として著者は、「現代技術に直面してのハイデガーの思索と問いの無力さ」(337)を語る。

「或る一つの東アジア的見地から見たハイデッガーの世界の問―集‐立と四方界」は、ハイデガーの思想をゲシュテレと四域の概念に基づいて、「東アジア」という視点から考察しようとするものである。

どれも最近の考察とは違う古さとある情緒を感じさせる文章である。

若見理江「カテゴリー的直観と時間性」--Webで読むハイデガー論(004)

タイトル:カテゴリー的直観と時間性 ---ハイデガーにおけるフッサールの志向性受容

筆者:若見理江

発表媒体:ハイデガー・フォーラム 第九回大会、レジュメ

発表年度:2014年9月21日

URL:http://heideggerforum.main.jp/data14/wakami_r.pdf

お勧め度: ■■■

寸評:カテゴリー的直観の概念にしぼって、ハイデガーがフッサールの志向性ま概念をどう受容したかを問いかける。問題提起だけだが、考えるヒントになる。

■ハイデガーの課題

ハ イデガーは、しばしばフッサールのカテゴリー的直観と自らの存在の問いとの関係について言及していた。しかし、とりわけフッサールのカテゴリー的直観につ いて詳細に取り上げている1925年夏学期講義『時間概念の歴史への序説』でも、カテゴリー的直観が具体的に『存在と時間』のどの部分に引き継がれている のかについて論及されておらず、ハイデガーの「存在」をめぐる問題との関係が不確かである。たしかに、フッサールもカテゴリー的直観に関連して「存在」を 語ってはいるが、それは繋辞「である」という意味での「存在」であり、またイデア的対象性としての「存在」である。つまり、『論理学研究』では「認識」が 主題とされているのに対し、『存在と時間』では「現存在の存在」が主題とされているのであって、フッサールのカテゴリー的直観が直接ハイデガーの存在の問 いに関係しているとは言い難い。

ハイデガーはギリシアに始まる西洋哲学の歴史を「存在忘却」によって特徴づけた。1925年の講義では、フッサー ルが「志向的なものの存在」を問わず、「存在の問い」を看過していることが指摘されている。だがその一方で、ハイデガーはフッサールの志向性を積極的に評 価しており、1923/24年冬学期講義『現象学的研究への入門』では、志向性の発見によって哲学史全体のなかではじめて徹底した存在論的研究のための道 が開かれたとも述べている。つまり、フッサールの志向性の研究によって存在を問うことが可能になったのだが、フッサール自身は存在を問うことはなかったと いう、ハイデガーの両義的な見方がある。

たしかに、志向性の発見はハイデガーに存在を問うための決定的な視点を提供した。しかし、フッサー ルの立場では繋辞の存在やイデア的対象性が示されるにとどまるのであり、さらに志向性およびカテゴリー的直観がもとづいているものを明らかにすることが必 要であった。それがつまり「時間性」であり、ハイデガーはフッサールの志向性に関する研究を軸にギリシア哲学やキリスト教思想を解釈するなかで、志向性は 時間性にもとづいているという観点を獲得していったと推察される。

1925年の講義では、現象学における三つの決定的な発見として「志向性」と 「カテゴリー的直観」と「アプリオリの根源的な意味」が取り上げられ、これらの考察によって「時間」が現象的に見えてくると言われている。カテゴリー的直 観は「志向性の具体化」であり、志向性もその具体化であるカテゴリー的直観も最終的には「時間」に引き戻されることが示唆されている。したがって、フッ サールのカテゴリー的直観とハイデガーが存在の問いのために要請するカテゴリー的直観とのあいだに見られる相違は、「現存在の存在の意味」である「時間 性」という観点を取り入れることによって説明可能となるように思われる。

■本稿の課題

明確にすべきことは以下の四点である。

第一に、ハイデガーにおいて「直観」は「理解」の派生態であり、カテゴリー的「直観」を「理解」から捉えることによってどのような違いが出てくるのかということ。

第 二に、フッサールにおいて「カテゴリー的直観」は「感性的直観」と対になる働きであるが、ハイデガーの存在の問いにおいて「感性的直観」はどのような扱い になっているのかということ。またこれと関連して、フッサールでは「カテゴリー的直観」と区別される「普遍的直観」は、ハイデガーにおいてどのような位置 づけになっているかということ。

第三は「カテゴリー的代表象」に関する点であり、フッサールはカテゴリー的直観のうちに感性的直観と同様に 「代表象」を認めていたが、のちに『論理学研究』第二版の序言では、「カテゴリー的代表象」についての理論をもはや是認しないと述べるにいたった。これに 対して、ハイデガーはフッサールのカテゴリー的直観を解説する際に「代表象」の問題について触れておらず、フッサールの以上のような「カテゴリー的代表 象」に対する考えの変化についても言及していない。ハイデガーにとっては、フッサールを煩わせた「カテゴリー的代表象」の扱いがそもそも問題にならなかっ たように見える。それはなぜなのかということ。

さらに第四として次の点が挙げられる。『論理学研究』において詳細に論じられていたカテゴ リー的直観は、その後の著作では主題化されなくなる。このことは、『論理学研究』以後のフッサールの現象学がハイデガーの存在の問いとまったく関係がなく なるということを意味しているのかということ。

以上の点について考察することによって、ハイデガーがフッサールのカテゴリー的直観とどこまで問いを共有し、どこから独自の解釈を施したのかということの境界が鮮明になり、ハイデガーのフッサールに対する両義的な態度の含意がはっきりしてくるように思われる。

リッケルト『認識の対象』を読む(1)

リッケルトの『認識の対象』は、ハイデガーがその著作で何度も引用している書物である。リッケルトはハイデガーを指導した教師であり、ハイデガーは リッケルトによって論理学の手ほどきをうけたことを感謝している。ハイデガーを理解するためには、リッケルトの新カント派の認識論を学ぶ必要があるだろ う。

以下では、リッケルトのこの『認識の対象』を原文対照で読んでいくことにしよう。ただし原文は、この書物の第一版であり、邦訳は第二版の訳である。ときおり、第二版の内容を追加しつつ読むことにする。

邦訳で参照したのは次の書物である。

認識の対象 (岩波文庫)

認識の対象 (岩波文庫)

第一章 認識論的な懐疑

Zum Begriff des Erkennens gehört außer einem Subjekte, das erkennt, ein Gegenstand, der erkannt wird. Unter Gegenstand verstehen wir das, wonach das Erkennen sich zu richten hat, um wahr oder "objektiv" zu sein. Was ist der Gegenstand der Erkenntnis?

認識する行為には、認識する主体のほかに認識する対象が必要である。そして認識の目的とは、認識が真であり客観的であるということである。問題なのは、認識の対象とは何か、「認識はどのようにしてその客観性を獲得するか」ということである。

Der "naive" Mensch sieht hier kein Problem. Gegenstände der Erkenntnis sind ihm die Dinge der Außenwelt, und wollte man von ihm eine Meinung darüber hören, worin ihre Erkenntnis bestehe, so würde er sagen, daß von den Dingen Vorstellungen in uns entstehen, und daß, wer mit den Dingen übereinstimmende Vorstellungen besitzt, die Dinge erkannt hat.

素朴な人は、認識の対象は外界の事物だというだろう。そしてわれわれは認識することで、その事物の表象をもつのだというだろう。

Auch von der Wissenschaft ist diese "naive" Erkenntnistheorie nur zum Teil verlassen. Allerdings meint man wohl, daß die Vorstellungen die Dinge nicht genau so geben, wie sie wirklich sind, sondern ihnen nur "entsprechen" oder sie "bezeichnen", aber daran hält man fest, daß Gegenstände der Erkenntnis Dinge sind, nach denen der Erkennende sich mit seinen Vorstellungen richten muß, wenn er erkennen will.

学においても、こうした素朴な考え方がみられる。認識の対象とは実在するか現実存在する事物であると考え、認識する者は表象で、これを捉えるのだと考えるのである。

Auch die Lehre des Denkers, der die letzte große Umwandlung in den Ansichten über das Erkennen hervorgebracht hat, glaubt man so deuten zu können, daß nach KANT das erkennende Bewußtsein einer Welt an sich existierender Dinge gegenüberstehe, deren "Erscheinung" es in sich aufzunehmen habe, um zur Erkenntnis der Welt zu gelangen. Der der naiven Meinung vom Erkennen zu Grunde liegende Gegensatz eines an sich vorhandenen Seins zu einem dieses Sein mit Hilfe der Vorstellungen erfassenden Bewußtsein bliebe hiernach auch durch KANT und somit überhaupt unangetastet.

カントもまた認識する主観である意識が、世界の事物の「現象」をその意識うちに取りこむ必要があると考えていた。カントの認識論でも、「自存する実在と、表象の力でこの実在を把握する意識の対立」は解決されなかった。

Läßt eine Erkenntnistheorie, welche auf diesem Gegensatz aufgebaut ist, sich durchführen, oder ist eine Umbildung des Erkenntnisbegriffes notwendig? Dies ist die Frage, zu deren Beantwortung wir einen Beitrag liefern wollen.

認識論の根本問題は、この対立をそのまま維持するか、それともこうした認識概念を根本的に革新しなければならないかということにある。

Wir heben zu diesem Zwecke von den Schwierigkeiten, welche sich für die herkömmliche Ansicht ergeben, zunächst die eine hervor, daß nicht nur die Erkennbarkeit, sondern auch die Existenz einer vom Bewußtsein unabhängigen Welt von Dingen in Frage gestellt werden kann. Offenbar ist dies eine Lebensfrage für jede Erkenntnistheorie, welche in einer solchen "außerhalb" des Bewußtseins existierenden Welt den Gegenstand der Erkenntnis sieht, denn falls die Existenz dieser "Außenwelt" mit Recht bestritten wird, gibt es keinen Gegenstand der Erkenntnis mehr. Die Untersuchung stößt damit auf das sogenannte Problem der Transzendenz: gibt es eine vom Bewußtsein unabhängige Welt?

伝統的な 認識論の第一の困難は、認識する主観からは独立した事物の世界があるのかどうかが決定できないことにあり、第二の困難はそうした世界が実在に存在するのか どうかを決定できないことにある。もしもこの外界の存在を疑うならば、認識の対象などは存在しなくなるし、認識はその客観性を失うだろう。この研究の重要 な課題は「認識する意識から独立した実在というものが存在するかどうか」を明らかにすることにある。

Eine neue Behandlung dieses Problems bedarf vielleicht einiger rechtfertigender Worte. Zwar kann man nicht behaupten, daß eine allgemein anerkannte Lösung bereits gefunden, und daher eine weitere Erörterung überflüssig sei. Trotzdem scheint das Interess an der Frage zu erlahmen. Einerseits gilt der Satz, daß das Wissen nicht weiter reichen könne, als das Bewußtsein reicht, für selbstverständlich, und damit muß die Existenz von Dingen außerhalb des Bewußtseins zum mindesten problematisch bleiben. Andererseits aber sind die Konsequenzen, welche sich aus jeder sich auf den Bewußtseinsinhalt beschränkenden Theorie zu ergeben scheinen, so ungeheuerlich, daß man dadurch allein die Annahme einer absoluten Wirklichkeit für gesichert hält. Man lehnt daher nicht selten den Zweifel an dieser Wirklichkeit als einen grundlosen oder "öden" unwillig ab. Im günstigsten Fall sieht man mit SCHOPENHAUER in dem theoretischen Egoismus oder Solipsismus eine kleine Grenzfestung, die zwar unbezwinglich ist, deren Besatzung aber auch nie aus ihr heraus kann, und die man daher ohne Gefahr im Rücken liegen lassen darf. Man tröstet sich mit dem Gedanken: auch wenn es keinen Beweis dafür geben sollte, so glaubt an die selbständige Realität der Außenwelt und seiner Mitmenschen im Grunde seines Herzens jeder Mensch.

この課題に関連して二点を指摘しておくべきだろう。一つは意識の外にある事物の存在は確実ではないという懐疑がはびこっていることである。しかしこの考 えは独我論を導かざるをえない。そのために、逆に外界の実存を疑うのは無益なことであると主張する人もいるのである。そしてショーペンハウアーの「理論的 独我主義」の砦にこもって、外界と他者の存在を証明することはできないが、心の中ではそれを信じて疑わないのだと広言するのである。

Man kann das zugeben und doch meinen, daß mit dieser Versicherung recht wenig geleistet ist. Wollte ein überzeugter Solipsist wirklich einmal den Versuch machen, als "Einziger" mit seiner Bewußtseinswelt als seinem "Eigentum" zu schalten, dann allerdings würden ihm gegenüber andere Maßregeln am Platze sein als wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen.

これは自分を「唯一者」と考えるものであるが、それは認識論の問題を解決するものではない。認識論にはこうした「信仰」の入る余地はないのである。

Aber dieser Umstand gibt keine Antwort auf die Frage, ob die Welt noch etwas anderes als Bewußtseinsinhalt ist. Man muß festhalten, daß man es hier mit einem erkenntnistheoretischen Problem zu tun hat, mit dem man daher nur auf dem Boden der Erkenntnistheorie fertig werden kann. Gerade für die Erkenntnistheorie aber gibt es keine Grenzfestungen, die man im Rücken liegen lassen darf. Und man muß ferner hervorheben, daß unter dem erkenntnistheoretischen Gesichtspunkt die sogenannte Frage nach der Realität der Außenwelt den Beigeschmack von Absurdität verliert, der an ihr nur deswegen haftet, weil mit den aus der Sprache des gewöhnlichen Lebens in die philosophische Terminologie hinüber genommenen Ausdrücken gewisse nicht zur Sache gehörige Vorstellungen mit in das Bewußtsein treten.

Allerdings ist zuzugeben, daß die Deutung der Welt als Bewußtseinsinhalt nicht immer aus rein erkenntnistheoretischen Gründen erfolgt ist. Mit Recht hat RIEHL (1) darauf hingewiesen, daß es oft "mißverstandene Forderungen unserer höheren geistigen Natur" sind, welche zum Idealismus führen, weil ihnen "die Erscheinungswelt niemals genügen kann", daß z. B. bei SCHOPENHAUER die pessimistische Weltanschauung als ein wesentlicher Faktor in der idealistischen Gestaltung seines Systems wirkte. Dieser Umstand darf jedoch nicht gegen die Berechtigung des erkenntnistheoretischen Idealismus verwertet werden. Er wird uns vielmehr nur dazu veranlassen, den erkenntnistheoretischen Zweifel an der absoluten Realität der Dinge von allen hedonischen, moralischen oder ästhetischen Erwägungen über Wert oder Unwert der Sinnenwelt abzusondern.

こうしたショーペンハウアーの理論からは、認識論的概念論は不要であろうか、学問としての認識論では、それに安住することはできないのである。

だから二つのことを区別する必要がある。一つは認識する意識に独立した事物の存在を認識論的に疑うという認識論の根本問題である。もう一つは意識に直接に 与えられた感覚世界の価値について、快楽論的に、道徳的に、美学的に、宗教的に評価することである。これがショーペンハウアーのしたかったことである。

Wir erinnern zu diesem Zweck an den Denker, der zum ersten mal das Problem der Existenz der Außenwelt in seiner ganzen Bedeutung erkannt und zu einem integrierenden Bestandteil seiner Philosophie gemacht hat. DESCARTES fand das zu seiner Zeit vorhande und von ihm erlernte Wissen unzuverlässig, und hatte daher das Bedürfnis, die Wissenschaft auf eine sichere Grundlage zu stellen. Um den Punkt zu gewinnen, von dem er bei seinem Vorhaben ausgehen konnte, machte er den bekannten Versuch, einmal alles zu bezweifeln, woran er bisher geglaubt hatte, um dann zu sehen, was er als schlechthin unbezweifelbar zurückbehielt. Die Existenz der vom Bewußtsein unabhängigen Welt war dem Zweifel zugänglich, sie mußte daher von dem in Frage gestellt werden, der sich vor jedem Irrtum schützen wollte. Der Weg zur absoluten Gewißheit konnte nur durch einen radikalen Zweifel hindurchgehen.

ところでこの認識論の根本課題で ある外界の実在性について考察し、体系の本質的な要素とした哲学者がいる。デカルトである。デカルトは哲学を確固とした土台の上に据えるために、懐疑を実 行して、外界の実在性を疑問にしたのである。それは絶対的な確実性への道は、根本的な懐疑によってしか開かれないと考えたからである。

ラスク「判断論」目次

ラスク「判断論」目次

- 標題 / (0004.jp2)

- 目次 / (0009.jp2)

- 緖論 / 1 (0011.jp2)

- 判斷が形式論理的・非對象的領域に屬すること / 1 (0011.jp2)

- 判斷の先驗論理的結構に對する關係 / 7 (0014.jp2)

- 判斷領域の對立性を超えて無對立性に進出し行くこと / 14 (0018.jp2)

- 對立對の二重性、卽ち、正理及び非理、眞理及び虛僞 / 18 (0020.jp2)

- 硏究の道程 / 39 (0030.jp2)

- ■第一章 判斷決定の第一次的客觀に於ける眞理と虛僞との對立 / 41 (0031.jp2)

- ■第一節 價値對立性の標識 / 42 (0032.jp2)

- 價値及び反價値は要素の相屬性及び不相屬性に外ならない / 43 (0032.jp2)

- 中性的『表象關繋』と繋辭 / 51 (0036.jp2)

- アリストテレースに於ける二重‐對立對說の萠芽 / 59 (0040.jp2)

- ■第二節 超文法的主辭・賓辭論 / 67 (0044.jp2)

- 文法的理論 / 69 (0045.jp2)

- 超文法的理論の標識 / 71 (0046.jp2)

- 槪念と判斷との水平化問題 / 73 (0047.jp2)

- 超論理的にではなく、論理的に方位決定する結構の必然性 / 75 (0048.jp2)

- 形式・質料-二重性 / 81 (0051.jp2)

- 認識の先驗論理的原始槪念 / 85 (0053.jp2)

- 範疇質料及範疇が眞實の主辭及び賓辭たること / 87 (0054.jp2)

- 超文法的理論によつて要求せられたる、文法的組織の變形 / 96 (0059.jp2)

- それに關聯して問題となり來るところの、槪念と判斷との水平化、並びに原始成素への槪念の分解 / 100 (0061.jp2)

- 繋辭と範疇的關係とが歸一しないこと / 111 (0066.jp2)

- 存在判斷 / 115 (0068.jp2)

- ■第三節 對立性の標識を眞正なる構造要素に適用すること / 119 (0070.jp2)

- 眞理及び虛僞が範疇と範疇質料との相屬性及び不相屬性に外ならぬこと / 119 (0070.jp2)

- ■第二章 超對立性 / 124 (0073.jp2)

- ■第一節 判斷造の技巧性、及びその對象的-論理的領域よりの距離 / 125 (0073.jp2)

- 先コペルニクス的見解が主張するとろの、原始形象的及ひ模寫形象的領域間の距離 / 126 (0074.jp2)

- コペルニクス的敎說内に於ても、この距離が從前通り存立すること / 131 (0076.jp2)

- 範疇的關係が決して相屬性でないこと / 136 (0079.jp2)

- 相屬及び不相屬が對象領域の摧破に基くこと / 141 (0081.jp2)

- 對象的構造が相屬性及び不相屬性の對を遠離してゐること / 145 (0083.jp2)

- まさしく範疇と範疇質料との間の相屬及び不相屬に於ける技巧性の特殊的昂進 / 150 (0086.jp2)

- 非對象的現象の論理學としての『形式』-論理學 / 166 (0094.jp2)

- カントに於ける、範疇の判斷形式に對する關係 / 174 (0098.jp2)

- 形式的論理學と先驗的論理學との區別によつて制約された形式槪念及び質料槪念の二重性 / 178 (0100.jp2)

- ■第二節 對立性の標準としての超對立性 / 185 (0103.jp2)

- 對象の超對立的妥當性及び價値性 / 185 (0103.jp2)

- 存在槪念の二義性 / 192 (0107.jp2)

- 對象的意味、眞理、認識、の槪念 / 197 (0109.jp2)

- 範疇の超對立的價値性 / 204 (0113.jp2)

- 意義分裂としての積極的價値及び反價値、價値の超對立性及びボックス・メディア / 211 (0116.jp2)

- アリストテレースに於ける超對立性の思想 / 216 (0119.jp2)

- カント、カント學派及び現代の論理的價値說に於ける超對立性思想の缺如 / 219 (0120.jp2)

- ■第三章 對立性の生起根據としての主觀性 / 235 (0128.jp2)

- ■第一節 眞理適應性及び眞理背反性の内在的根原 / 235 (0128.jp2)

- 内在化と内在性 / 236 (0129.jp2)

- 主觀性による對象領域の掘鑿 / 241 (0131.jp2)

- にも拘らずその際維持せられるところの意味の擬超越性 / 245 (0133.jp2)

- 被造的意味の理論に於ける意味問題と主觀問題との交涉 / 251 (0136.jp2)

- ■第二節 判斷決定に於ける肯定及び否定、正理及び非理 / 257 (0139.jp2)

- 相對的に無對立的なる標準としての眞理適應性及び眞理背反性 / 257 (0139.jp2)

- 技巧性及び摧破作用の更に進める段階、表象關繋或は『意味斷片』 / 261 (0141.jp2)

- 「然り」及び「ならず」を含む意味 / 271 (0146.jp2)

- 繋辭 / 275 (0148.jp2)

- 積極的及び消極的判斷の同格視 / 277 (0149.jp2)

- 正理及び非理の構造 / 280 (0151.jp2)

- その擬超越性 / 285 (0153.jp2)

- 價値無差別的『意義』としての『槪念』 / 289 (0155.jp2)

- 對立問題との關係に於ける規範槪念 / 294 (0158.jp2)

- 肯定及び否定が意味の主觀-雙關者たること、疑問、蓋然的態度及び確實性程度が單なる主觀性の區別なること / 299 (0160.jp2)

- 價値對立の更に一般的なる問題への指示 / 307 (0164.jp2)

- 人名索引 / (0165.jp2)

- ラスクのひととなり リッケルト / (0166.jp2)

リッケルト紹介、スタンフォード哲学百科から、長文

Heinrich Rickert (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Heinrich Rickert

Heinrich Rickert was born in Gdańsk (then Danzig, in Prussia) on May 25th 1863. His father Heinrich Rickert Sr. (1833–1902) was a politician and editor in Berlin. Heinrich Sr. was a liberal democrat particularly invested in the cause of the German Jews. In 1890 Heinrich Sr. founded the Society Against Anti-Semitism in Berlin (Zijderveld 2006, 9). This is an interesting fact about Rickert Jr.'s background, considering that he eventually worked to support the appointment of philosophers of Jewish descent, such as Edmund Husserl and Georg Simmel, who were not under the protective wing of Hermann Cohen, the head of the Marburg School of Neo-Kantianism (see below) and a very influential Jewish thinker.

Between 1884 and 1885 Rickert was enrolled at the University of Berlin, where he attended lectures from the philosopher Friedrich Paulsen (1846–1908). In 1885 he moved to Strasbourg (then Straßburg and part of the Prussian Reich) where he attended the Neo-Kantian philosopher Wilhelm Windelband's lectures. Windelband (1848–1915) was a major source of inspiration for Rickert's work and he completed a dissertation on The Theory of Definition (Rickert 1915) under Windelband's supervision in 1888. In the same year he married Sophie Keibel, a sculptor from Berlin. They had four children.

In 1889 Rickert moved to Freiburg for health-related reasons. Rickert's health was always precarious. After undergoing intestinal surgery in 1896 he suffered lifelong intercostal neuralgia and he developed agoraphobia. In spite of his health problems, Rickert was able to complete his Habilitation under Alois Riehl (1844–1924) in Freiburg, where he was appointed extraordinary professor in 1894 and ordinary professor in 1896. The dissertation he produced for the Habilitation, The Object of Knowledge, is one of his most important works and a milestone in early twentieth century Neo-Kantianism.

Rickert remained in Freiburg until 1915, when he accepted an offer from the University of Heidelberg to replace his recently deceased mentor Windelband, who had moved there from Strasbourg in 1903. He taught in Heidelberg until 1932, when he retired. He died on July 25th 1936 in Heidelberg and was buried in Gdańsk.

Rickert had a long and successful academic career. He received several awards and honorary degrees. He taught and in some cases supervised important German thinkers of the next generation, such as Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), Emil Lask (1875–1915) and Walter Benjamin (1892–1940). He had close intellectual exchanges with leading figures of his time, including Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911), Georg Simmel (1858–1918), Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), Max Weber (1864–1920) and Karl Jaspers (1883–1969). Although very few of his writings are available in English, in recent years there has been a growing interest in Rickert's work, both to the extent that it influenced other philosophers and as a significant contribution to the discipline in its own right.

Rickert was a very prolific writer. He managed his publications in a way that should strike the contemporary reader as familiar. He would present new ideas and lines of inquiry first in exploratory journal articles (many of them published in Logos, the journal he founded in Freiburg) and subsequently he would incorporate them in larger publications, often including previously published materials. Following a common trend in his time, he kept working at his two major books, The Object of Knowledge (first published in 1892) and The Limits of Concept-Formation in Natural Science (first published in 1902), for his entire life. Instead of writing new books he would rewrite entire chapters and add new sections to his two magna opera, thereby addressing criticism and sometimes even changing significantly his previous views. So, for instance, The Object of Knowledge grew from the 91 pages of the first edition to the 460 pages of the sixth edition in 1928. This style of writing makes the development of his thought particularly perspicuous. However, in spite of his constant revisions and additions, the fundamental principles of Rickert's philosophy remained constant throughout his career. In keeping with his systematic understanding of philosophy (see below), his approach to new problems was geared towards connecting them to old problems, and his way of handling criticism was often characterized by an effort to reformulate his opponent's views so as to make them compatible with his own.

- 1. Southwestern Neo-Kantianism vs. Marburg Neo-Kantianism

- 2. Theory of Knowledge

- 3. Theory of Science

- 4. The philosophy of values and the philosophy of history

- 5. Metaphilosophy

- 6. Ontology and Metaphysics

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Southwestern Neo-Kantianism vs. Marburg Neo-Kantianism

Rickert is considered the head of the so-called Southwestern or Baden school of Neo-Kantianism, whose exponents worked in the philosophy departments at Freiburg and Heidelberg, both in the region of Baden in southwestern Germany. The Southwestern school stands in contrast to the so-called Marburg school, spearheaded by Hermann Cohen (1842–1918) and continued by Paul Natorp (1854–1924) and Ernst Cassirer (1874–1945). (For an overview of the two schools see Crowell 1999.)

In spite of their fierce opposition, the two schools present elements of similarity alongside the numerous elements of difference. These have been recently debated among Neo-Kantianism scholars (Krijnen 2001, 77–93; Krijnen/Noras 2012). One indisputably common element between the two schools is the preoccupation with the problem of validity, or Geltung, which is arguably the systematic core of Neo-Kantianism in general (Krijnen 2001, 84). Philosophy for the Neo-Kantians is concerned with the systematic elucidation of the a priori principles that allow for valid thinking in various spheres of knowledge. In keeping with Kant's first Critique, valid thinking is not merely logically consistent thinking. Valid thinking requires, over and above the adherence to the laws of formal logic, thinking in accordance with the a priori principles governing the intelligibility of a given area of reality. These will be, for instance, the principles of causality, substantiality etc. in the sphere of physical nature and principles such as good and evil, responsibility, freedom, etc. in the sphere of ethics. It is the task of philosophy to identify these a priori principles in all the different spheres of culture, including politics, biology, art, history, etc. Helmuth Plessner captures metaphorically the spirit of Neo-Kantianism when he characterizes the Neo-Kantians as “botanists in the garden of the a priori” (Plessner 1974, 185).

In their attempt to clarify the way in which we should think of such principles, both the Southwestern and the Marburg Neo-Kantians reject any kind of psychological reading, which dominated among early 19th Century interpretations of Kant. The a priori principles of valid thinking are not mere facts about human psychology; they do not describe merely how our mind happens to function. Their validity is objective, that is, it is part of the formal structure of the objects of investigation and not merely an extrinsic mental scheme that exemplars of the species homo sapiens contingently apply to them.

Moreover, both schools were rather unenthusiastic about the label ‘Neo-Kantianism’. Their goal was not to go “back to Kant”, as Otto Liebmann (1840–1912) famously urged philosophers to do in his Kant und die Epigonen (Liebmann 1865), but, rather, to move forward beyond Kant building on his original views. Windelband, Rickert's mentor and the forefather of Southwestern Neo-Kantianism, pronounced: “To understand Kant means to move beyond him” (Windelband 1915, IV). Likewise, the Marburg school leader Cohen pointed out: “From the very beginning I was concerned with developing Kant's system further” (Cohen 1902, VII).

The two schools, however, diverge significantly in their interpretation of Kant. While the Marburg school was predominantly interested in the Critique of Pure Reason (Cohen 1885) and considered it to be an essay in the philosophical foundation of Newtonian science (a reading that is still prominent among contemporary Kant scholars, such as Friedmann 1992), Rickert and the Southwesterners emphasized the importance of reading Kant as a whole and considered the centerpiece of his philosophical program to be the system of the faculties outlined in the introduction to the Critique of Judgment (Rickert 1924b, 167). For Rickert, in particular, already in Kant's first Critique “the focal point […] is not in the transcendental aesthetic and analytic but rather in the dialectic, and this means that the main problem of this work is not a theory of the experiential sciences (Erfahrungswissenschaften). Rather, it revolves around the old, ever-recurring problems of metaphysics. The work on these problems becomes the foundation for an encompassing theory of worldview culminating in the treatment of issues in the philosophy of religion. The theory of mathematics and physics is merely preparatory for the treatment of these issues” (Rickert 1924b, 153). Rickert's Kant is primarily a philosopher of human culture at large, interested in questions about the meaning and value of our life in the world, whereas Cohen's Kant is primarily (albeit not exclusively) a philosopher of the natural sciences. Incidentally, the largely ignored influence of Rickert's Kant-interpretation is still vivid in Heidegger's acclaimed book Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics (Heidegger 1997).

From these diverging interpretations of Kant flows another fundamental theoretical difference between the two schools. This difference has been effectively phrased by Rickert's student, Emil Lask in terms of “pan-logism”, attributed to the Marburg Neo-Kantians, versus the “pan-archy of logos”, attributed to the Southwestern Neo-Kantians (Lask 1923, 133; Crowell 2010). If we take the distinction between intuition (Anschauung) and concept (Begriff) to be the fundamental paradigm of Kantian transcendentalism, then in Lask's eyes the Marburg Neo-Kantians are committed to a kind of ‘pan-logism’ to the extent that they tend to minimize the role of intuition. As is particularly evident, for instance, in Natorp (1911, 26–67), for the Marburg Neo-Kantians whatever we might be tempted to consider a pure given or a raw datum of experience can be analyzed into an underlying thought-process, whereby the given is actually constructed according to a conceptually articulable (i.e., logical) pattern. Every alleged pure given (Gegebenes) is actually a task (Aufgegebenes) for conceptual thinking and can be resolved into an underlying thought process governed by logical a priori principles.

Contrariwise, Rickert and the Southwestern Neo-Kantians emphasize the ultimate irreducibility of what is given in intuition to conceptual forms. While everything can be grasped by concepts, and therefore no domain of reality and cultural life eludes in principle conceptual mastery (pan-archy), nothing can be grasped exhaustively by concepts, and therefore our rationality has to constantly take into account an irrational residue intrinsic to every conceptual construction. To conceptualize, for Rickert, is to recast the materials delivered immediately by the senses into a conceptual form. In so doing, we necessarily have to be selective, that is, we have to leave out of consideration an overwhelming amount of elements and take up in our conceptuality only those elements that match the criteria originally established for the purpose of solving our theoretical task. To give a simple example, in order to conceptualize, say, linear motion we have to isolate from the overwhelming amount of data stemming from the senses only those features that pertain to the movement of bodies (spatial location, speed, reciprocal position, etc.) and leave out of consideration everything else. This general characterization can serve as a prelude to Rickert's theory of knowledge, which is the theme of the next section.

2. Theory of Knowledge

For us, epistemology has become a matter of good conscience, and we will not be prepared to listen to anyone who fails to justify his ideas on this basis. (Rickert 1986, 21)

For Rickert epistemology or Erkenntnistheorie (‘theory of knowledge’) has to be the point of departure and the systematic foundation of philosophy as a whole. He often uses interchangeably the words “logic” (Logik), “theory of knowledge” (Erkenntnistheorie), “methodology” (Methodologie), “theory of truth” (Wahrheitslehre) and “theory of science” (Wissenschaftslehre). (See for instance Rickert 1986, 19; Rickert 1909, 170.) This is because ultimately all these phrases refer to one and the same problem, i.e., the problem of the validity of thought and the principles on which valid thought rests. Erkenntnistheorie, therefore, is his preferred phrase because it makes this fundamental problem most explicit.

Rickert's theory of knowledge is designed to answer the following question: “what is the subject-independent yardstick of knowledge? In other words, through what does knowledge receive its objectivity?” (Rickert 1921a, 1) Or, following the title of his major work in the theory of knowledge, what is the object of knowledge? In asking this question Rickert is explicitly setting up a transcendental argument that can be summarized as follow: given that (1) there is knowledge and that (2) knowledge as true thought can be contrasted to mere thought in that it grasps some thought-independent object, how are we to think this thought-independent object? (Rickert 1909, 170) Therefore Rickert rejects the idea that the theory of knowledge should somehow respond to skepticism (Rickert 1921a, 7; Rickert 1909, 174). To the extent that skepticism negates the very possibility of knowledge it cannot be meaningfully addressed in a theory that sets out to determine precisely what knowledge is. Nonetheless Rickert believes that a modified version of skeptical doubt, which he compares to Husserl's epoché (Rickert 1921a, 12), is beneficial to the theory of knowledge. The theory of knowledge cannot begin without some presuppositions, in particular, that there are true thoughts in which a subject successfully grasps an object. “However, the theory of knowledge ought to be ‘presuppositionless’ in the sense that it ought to limit as much as possible the presuppositions upon which the objectivity of knowledge rests” (Rickert 1921a, 12). It is through the exercise of doubt that we get to raise the key question as to whether we necessarily have to posit a transcendent reality existing independently of consciousness as the source of validation for knowledge. The pursuit of the object of knowledge, then, leads straight to the problem of transcendence and its relation to the knowing subject. Note that Rickert is not questioning one of the inescapable assumptions of any theory of knowledge, namely, that there has to be some subject-independent yardstick or criterion that validates knowledge. He is questioning whether this subject-independent criterion has to be understood as a transcendent reality, for instance, a world of mind-independent and presumably physical things in themselves. His conclusion will be precisely that this transcendent criterion cannot be meaningfully conceived of as a reality and that only values can be considered genuinely transcendent.

Rickert argues that we can tackle the problem of the theory of knowledge in two ways: “One can begin first with an analysis of the real act of knowledge as a psychic process and then, from there, move progressively to determine the transcendent object. Secondly, one can attempt to reach as quickly as possible the sphere of the transcendent object and deal with it in a purely ‘logical’ fashion without considering the psychic act of knowing” (Rickert 1909, 174). He labels these two approaches the “transcendental-psychological” (or subjective) and the “transcendental-logical” (or objective) ways (Rickert 1909, 174). While in the first editions of The Object of Knowledge Rickert privileged the transcendental-psychological way, in the early 1900s he introduced the transcendental-logical way and incorporated it into later editions of the book, arguing that the two ways should be considered complementary.

The most important move at the beginning of the subjective way is to determine the notions of subject and object that the theory of knowledge can legitimately operate with, and, in particular to characterize “the epistemological subject” (das erkenntnistheoretische Subjekt) (Rickert 1921a, 41). Rickert examines three different subject/object dichotomies. (1) We can define the object in spatial terms as what is out there in the world. This is what the expression ‘external world’ seems to refer to. Correspondingly, the subject, too, will be defined in spatial terms as the animated body, for which there are spatial surroundings populated by objects. The first dichotomy construes subject and object as “two bodies” (Rickert 1921a, 14) facing each other in physical space. (2) We can construe a second dichotomy, in which we take our body, too, to be an object like other objects and consider ‘subject’ to refer exclusively to consciousness. “In this second case my consciousness and its content are the subject, and therefore the object is everything that is not my content of consciousness or my consciousness itself” (Rickert 1921a, 15). This second dichotomy captures the traditional distinction between immanence and transcendence. (3) A third dichotomy ensues from a further distinction that we can carry out within the sphere of immanence, that is, the distinction between the ego and its representations, or between any content of consciousness and consciousness itself. In this third case representations, perceptions, feelings, emotions etc. would be the object and the subject would be the ego standing over against them.

Based on these dichotomies, it seems that the problem of transcendence and its possible denial only pertains to (2). It would not make sense to question the transcendence of the object if by object we mean what occupies the spatial surroundings of a psychophysical human subject and, similarly, it would not make sense to deny the transcendence of our representations, perceptions, emotions etc. from the point of view of the pure ego-subject undergoing such representations, perceptions, emotions, etc. Following the subjective way, we should then set out to determine whether we necessarily have to posit the existence of transcendent objects independent from the contents of our consciousness. We should, it seems, assume what the positivists have called “the standpoint of immanence” (Rickert 1921a, 21) and see if there is some rationally justifiable way to infer our way out of it.

This conception however, is misleading and if we took it as our point of departure it would put the whole enterprise of the theory of knowledge in jeopardy. Who or what is the subject, for which the problem of transcendence can be meaningfully posed? Rickert indicates that the three concepts of subject considered above ought to be seen in their mutual relations. If we begin with the psychophysical subject in (1), we can obtain the notion of subject in (2) by way of a progressive ‘objectification’ of the body (Rickert 1921a, 35). I can progressively consider each part of my body as itself an ‘object’ or content of my consciousness and once the whole body has been ‘purged out’ the result will be a purely psychic subject, which Rickert defines as “the limit concept (Grenzbegriff) of the series, in which the physical component in the subject becomes progressively smaller” (Rickert 1921a, 36). In a similar way, we can continue the process of ‘de-objectification’ of the subject and consider each and every mental state as itself an object for an absolutely non-objective and non-objectifiable ego. In this way we reach the authentic epistemological subject, the identical “subject-factor” (Rickert 1921a, 42) that provides the form ‘subjectivity’ to every possible content of consciousness. Following Kant's terminology Rickert designates the epistemological subject “consciousness in general”, that is, a “nameless, generic, impersonal consciousness” (Rickert 1921a, 42). This consciousness in general has to be distinguished sharply not only from the individual psychophysical human subject but also from the individual psychic subject with its empirical mental states.

Rickert insists: “The question regarding immanence or transcendence only makes epistemological sense with respect to the epistemological subject or consciousness in general” (Rickert 1921a, 43). From this perspective, “to be immanent means nothing but to carry the form of being-conscious (Bewußtheit) and to be transcendent means to really exist without such form” (Rickert 1921a, 48). Given these definitions, Rickert contends that while there are many good reasons to reject psychological idealism, if one holds fast to consciousness in general there is no good reason to posit the existence of a transcendent reality beyond the sphere encompassed by the epistemological subject. His theory of knowledge is therefore committed to transcendental idealism. In order to defend this point Rickert examines three types of arguments that have been traditionally played out against transcendental idealism as defenses of the necessity to posit a transcendent reality: (1) transcendence as the unexperienced cause of conscious experiences (Rickert 1921a, 62–73); (2) transcendence as necessary in order to fill the gaps in our conscious experiences (Rickert 1921a, 74–84); (3) transcendence as the objective counterpart of our will, that is, as the correlate of the experience of a resistance and constraint to our willful actions (Rickert 1921a, 84–93). All these arguments, however, only show that we cannot reduce reality to psychic existence. In other words, they are good arguments only against a psychological idealism à la Berkeley according to which reality would coincide with our empirical mental states. From the point of view of the epistemological subject, however, both psychic and physical occurrences are objects whose reality is encompassed by the form ‘consciousness in general’. A transcendental idealist, then, emphatically agrees that there is an extra-mental physical reality causing the occurrence of mental states in empirical subjects. To the extent that they are experienced or experienceable, however, both extra-mental (physical things) and intra-mental realities (mental states) have to be seen as content of consciousness, namely, of transcendental consciousness in general. It is important to remember that by ‘consciousness in general’ Rickert means no individual psychic subject but the general form of subjective accessibility. In other words, to say that all reality is a content of consciousness does not mean that all reality is psychic. It means that all reality (both psychic and physical) is encompassed by a general form of subjectivity, which makes it available for theoretical determination. Commenting on his own brand of transcendental idealism, Rickert states: “our standpoint is the true realism” (Rickert 1921a, 104), in that it refuses to counterpose an immanent psychic reality to an inaccessible transcendent reality to be posited via inferential reasoning. Rickert insists that transcendental idealism considers real precisely the reality that we encounter in everyday life through sensory experience, consisting of immediately aware psychic and physical occurrences. What it rejects is that this reality can be meaningfully construed as transcendent vis-à-vis consciousness in general.

The reason why one might be prone to reject transcendental idealism is a wrong conception of what knowledge really is all about. Rickert labels this conception the copy-theory or pictorial theory (Abbildtheorie) of knowledge. According to this conception, “the act of knowing has to depict (abbilden) a reality independent from its activity of representing (vorstellen)” (Rickert 1921a, 119). The rejection of a pictorial theory of cognition and the ensuing intuitionism (according to which to know is merely to intuit some mind-independent real or noetic object), remains a constant in Rickert's philosophy (see Rickert 1934a; Staiti 2013a). It also connects Rickert with other Neo-Kantians, including Natorp and Cassirer in Marburg, who likewise reject the notion that knowledge is a merely picturing representation of the object (see Holzey 2010; Kubalica 2013).

In order to expose the untenable notions in the pictorial theory of knowledge Rickert introduces a distinction between the form and the content of cognition. While nothing is wrong with the idea that in order to have knowledge we have to take up in some representations some content, what distinguishes knowledge from other kinds of representation must be sought in its form. If I say of a piece of paper that it is white, then certainly “my representation reproduces what is real with respect to the white, and this is why the statement is true” (Rickert 1921a, 125). However, this is not all. “In the statement at issue (this piece of paper is white), in fact, not only is the being-white asserted alongside the being-white, but rather, the white as ‘property’ is also attributed to a ‘thing’, and, in so being, the being-white is determined more specifically. Thing and property, however, are, as much as being and reality, concepts that do not belong in the content of knowledge. One has to know beforehand what it means epistemologically that a ‘thing’ has a ‘property’ and what the objectivity of this piece of knowledge rests upon in order to be able to say: ‘the thought: this piece of paper is white grasps what is real through pictorial representations” (Rickert 1921a, 125–126; Rickert 1909, 177). The theorist of knowledge cannot overlook the gulf that exists between the pre-discursive perceptual experience of seeing a white piece of paper and the articulation of the true judgment ‘this piece of paper is white’. The judgment does not merely mirror or depict perceptual reality. Rather, the judgment transforms and reshapes the perceptual material delivered by the senses by way casting it into a new form, whose legitimacy does not rest in the faithful depiction of the perceptual scene but in the logical validity of such forms. The problem of the pictorial theory of cognition is that it “ignores the form” (Rickert 1909, 178).

These considerations lead to one of the key theses in Rickert's theory of knowledge: “The fundamental problem of the theory of knowledge is the question regarding the yardstick or the object of judging (Rickert 1921a, 131–132). The epistemological subject is not merely a representational subject, but rather a judging subject. Judgment is for Rickert the place where the standpoint of immanence is necessarily broken and the genuine meaning of transcendence becomes manifest. In his analysis of judgment Rickert draws a sharp distinction between the psychological act of judging and the content (Gehalt) of a judgment, which parallels Husserl's treatment of the same issue in Logical Investigations (Husserl 1973). While the act of judging, say, that 2 + 2 = 4 is a psychic occurrence unfolding in time and differing for each empirical subject making this judgment, the objective content grasped by this act, the true relation 2 + 2 = 4 is timelessly valid and it is one over and against the many psychic acts directed towards it. Moreover, if by real we mean either a psychic or a physical entity, then the content of the judgment 2 + 2 = 4 has to be deemed “unreal” (Rickert 1921a, 145). Taking notice of the objective content of an act and reflecting back on the psychological act of judging that intends such content we also have to highlight a third component of a judgment, which Rickert labels “immanent sense” of the act (Rickert 1921a, 145), i.e. that which orients the act towards the judged content. As one commentator puts it: “the immanent sense of the judgment stands in an intermediate position between the real psychic act and the unreal logical content” (Oliva 2006, 97). It is the function (Leistung) performed by the psychic act seen purely and exclusively in its functionality of connecting psychological subjectivity and logical objectivity. Determining what kind of immanent function characterizes judgments and how this function sets them apart from other kinds of psychic occurrences is Rickert's next step.

In order to grasp the epistemological essence of judgment and its relation to the fundamental epistemological problem of transcendence we have to describe its difference from a mere representation or string of representations. The best way to characterize the specific essence of judgment is by “considering the judgment the answer to a question” (Rickert 1921a, 153). Rickert thus identifies the essence of judgment is thus in the function of “affirmation or negation” (Rickert 1921a, 154), thereby following a trend in logic that dates back to Brentano (see Brentano 1995, 194–234). If we consider exclusively the representational content, the judgment, “this paper is white”, and the question, “is this paper white?” do not differ in the slightest. The same representational elements are there in a meaningful connection. The genuine performance of judgment, for Rickert, is all contained in the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ that we could answer to the question, thereby taking a stance with regards to the represented content. In fact, what distinguishes judgment from all sorts of representations is the moment of ‘stance-taking’ (Stellungnehmen) expressed by the words ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Judging should then be considered a “practical comportment (Verhalten)” (Rickert 1921a, 165), in which something is acknowledged as true or rejected as false. In this regard, judging has to be considered an “act of valuing” (Rickert 1921a, 165). What is it, however, that elicits from the epistemological subject an act of stance-taking? Rickert explains: “With our act of affirming we can only orient ourselves toward requirements (Forderungen), only vis-à-vis a requirement can we comport ourselves in an endorsing fashion. In this way we have obtained the broadest concept for the object of knowledge. What is known, that is, what is affirmed or acknowledged in the act of judgment must be located in the sphere of the ‘ought’ (Sollen)” (Rickert 1909, 184). This is the kind of transcendence that Rickert set out to determine at the beginning. The object of knowledge has to be conceived as transcendent, however, not as a transcendent reality mirrored by a psychological act of representation but as a “transcendent ought” (Rickert 1909, 187). This prompts the theoretically oriented subject to affirm the transcendent theoretical value of truth in the necessary connection existing between the form and the content expressed in a true judgment.

Examining retrospectively the results of this first subjective path of the theory of knowledge Rickert points out a number of shortcomings. It seems that if we begin with an analysis of the act of judging, we can only reach the transcendent object of knowledge by way of a “petitio principii” (Rickert 1909, 190). If we take our cues from the psychologically perceived “feeling of a requirement” (Forderungsgefühl) and from the evidence of the judged content as the “immanent indicator of the transcendent” (Rickert 1909, 189), we have no sufficient reason to posit a transcendent object of knowledge unless we somehow already presupposed it in the very analysis of this feeling and its psychological connotations. It seems that the only conclusion we could legitimately draw without falling into circular reasoning is that when a certain compelling feeling of evidence occurs, we feel the urge to affirm the truth of a certain connection between a form and a content. But this does not really amount to proving that the internally felt sense of ought is connected to a transcendent ought. Rickert considers petitio principii inherent in the subjective path to be problematic but nonetheless a useful starting point, in that it allows us to analyze the meaning of certain fundamental concepts of the theory of knowledge such as transcendence, ought, stance-taking and recognition. However, in order to have a complete theory of knowledge, an objective or transcendental-logical path has to be taken.